Institutional Roles & Program Approval

Academic Program Approval and Review within USHE

The Utah System of Higher Education uses clearly defined institutional roles and geographic services regions to ensure that residents have access to quality higher education program offerings. Specific roles define the types of instructional programs that institutions may offer, and geographic services regions define which institutions have primary responsibility for higher education within individual counties. The combination of roles and services regions helps to ensure equitable distribution of educational opportunities across the state while also ensuring that there is no unnecessary and costly duplication of programming, especially by institutions within close proximity to each other.

Institutional Roles

Utah State Code defines four different roles for institutions within the Utah System of Higher Education (USHE). It assigns the Board of Higher Education the responsibility of defining the types of academic or instructional programs that may be offered within those institutional roles. Board Policy R312 defines:

- the level of program and types of credentials (certificates and degrees) that institutions with a particular role may offer;

- special characteristics of the institutional role, such as whether it may have selective admissions or open admissions;

- broad fields of study that are within the institution’s specific mission; for example, veterinary doctoral programs being assigned to Utah State University and medical doctor programs assigned to the University of Utah.

The four institutional roles within the USHE are:

- Technical Colleges: The system’s technical colleges provide “technical education,” or occupationally-focused short-term, certificate-based training programs that are offered at a highly subsidized tuition rate. Because the geographic service regions of individual technical colleges overlap with regional universities, the technical colleges are prohibited by state law from offering general education programs or classes that would unnecessarily duplicate degree programs. The institutions authorized to provide technical education are Bridgerland, Ogden-Weber, Davis, Uintah Basin, Tooele, Mountainland, Southwest, and Dixie Technical Colleges, and the technical college units within Salt Lake Community College, Snow College, and Utah State University.

- Community Colleges: The two community colleges, Salt Lake Community College and Snow College, provide career and technical education and transfer associate degree programs and are open-access institutions. Both also include a technical college unit and offer technical certificates.

- Regional Universities: The four regional universities are authorized in state code to provide career and technical education, undergraduate associate and baccalaureate programs, and select master’s degree programs to fill regional demands. These include Weber State University; Southern Utah University; Utah Tech University; and Utah Valley University. Each institution has a specific focus identified in its mission statement, such as SUU’s emphasis on experiential learning and Utah Tech’s polytechnic focus. All are required to be open-access institutions and fulfill the community college, but not the technical college, role for their geographic service regions. The “career and technical education” (CTE) responsibilities assigned to regional universities in state code are primarily associate degree programs and are linked to eligibility for special federal Perkins CTE funding but should not duplicate instructional programs offered by the technical colleges.

- Research Universities: State code specifies that only the University of Utah and Utah State University may be classified as research universities, which are authorized to provide undergraduate, graduate, and research programs. The Board has further clarified the missions of both institutions, with Utah State University serving as the state’s Land Grant and Space Grant institution and the University of Utah housing the state’s only medical school. As research universities, both institutions are highly selective in their student admissions standards, although USU also includes community college and technical college units with open admissions processes through its Price, Blanding, and Moab campuses.

Presidents and Boards of Trustees are able to determine specific institutional mission statements within their defined role, which are then approved by the Board of Higher Education. These mission statements are updated periodically to reflect the strategic plans of the institutions, roughly about every 5-6 years.

Geographic Service Regions and Program Offerings

State code specifically calls for the Board to “develop strategies for providing higher education, including career and technical education, in rural areas” (53b-1-402). As a result, the Board has encouraged a system of robust colleges and universities across multiple geographic regions in order to fully meet the needs of the state.

The Board assigns geographic service regions to each institution through Policy R315 and gives institutions the primary responsibility for ensuring broad and adequate access to higher education within their regions. USHE institutions are not allowed to offer programs within another institution’s region unless approved by the Board of Higher Education, with the exception of technical colleges, whose service regions overlap with universities. Institutions may receive permission from the Board to provide programs outside their service area if the primary institution is unable or unauthorized to provide a specific type of program (such as a doctoral program) or if the institutions are working in partnership to jointly provide a program. Online education is not bound by geographic regions and is open to students throughout the state.

The importance of a breadth of offerings within service regions was highlighted in a 2019 report commissioned by the state legislature and completed by the National Center for Higher Education Management Consulting (NCHEMs). Distinctive cultural patterns in Utah affect where students choose to go to college and, therefore, the types of programs the Board should ensure will be offered by USHE institutions. Those Utah patterns include:

- The tendency to delay college enrollment after high school graduation, particularly associated with LDS missionary service and a desire to work first to avoid debt for college (NCHEMs 4).

- Loan aversion and a lack of state grants or other means of addressing affordability for middle-income families, which means many students work while attending school and consequently delay enrollment, attend school part-time, and extend their time to graduation.

- A higher and younger marriage and parenting rate than in other parts of the country, which results in many students, especially women, delaying or postponing degree completion.

- A pronounced disinclination for Utah students to attend institutions far from home. The report notes, “Enrollments of Utah residents, even at the University of Utah, are predominately comprised of students who live nearby, although some [institutions] do attract students from other states or countries. Perhaps somewhat surprisingly, Snow College turns out to be the most geographically diverse USHE institution, at least in terms of serving Utahns in large proportions from many counties. Meanwhile, the University of Utah effectively recruits non-residents from other states with its substantial national presence and brand name, but Utahns in attendance—nearly half of its total undergraduate students and over 60 percent of its resident students—are predominately from the institution’s home county. In other words, so long as Utahns stay in-state for college, they are likely to enroll at a local option. This has major implications for where capacity has to be provided, especially in the context of localized rapid population growth” (NCHEMs 18).

The NCHEMs report urged the Board to be mindful of these patterns and to ensure an appropriate range of program and degree offerings at USHE institutions in order to provide Utahns with access to comprehensive educational offerings wherever they may live (NCHEMs 4, 19).

In terms of the types of programs USHE institutions should offer, the NCHEMs report noted that the stakeholders interviewed for the study were “generally satisfied with the availability of graduates at the baccalaureate level,” but noted a consistently critical need for teachers and healthcare workers across the state. Although it encouraged the Board to anticipate unmet demand for specific, highly focused programs, including “aeronautical engineers, computer science and related engineering disciplines,” it also noted that those occupational needs may be clustered in particular geographic regions rather than widespread across the state. It emphasized the critical need in rural communities for workers who are broadly trained via associate and bachelor’s degrees rather than being focused too narrowly on specific occupational skills. The report also highlighted the state’s demand for academic programs that will help individuals grow and build their own small businesses rather than entry-level work in existing occupations. (NCHEMS 30)

The NCHEMS study made the following suggestions about program offerings:

- “Programs should strike an appropriate balance between the specific and the general, reflecting the fact that occupations in remote locations are likely to demand a broader range of skills, knowledge, or expertise from fewer workers, as opposed to highly specialized occupations, such as technical certificates or professional graduate degrees, in more populated areas.

- “Meeting a rural area’s need for some academic programs may be fulfilled by a periodic single cohort rather than a steady supply. Program cohorts may need to be built collaboratively among prospective students across the state.

- “Programs should be stackable and credits transferrable” between USHE institutions (NCHEMS 57-58).

Because the investment in new programs may be substantial or may have limited workforce demands, some programs are not widespread throughout the system and are restricted to particular institutions on the basis of their mission. The University of Utah, for example, is a selective institution and, as such, does not invest many resources in remedial or development education for underprepared students, as the community colleges and regional universities would do. However, as the system’s flagship institution and only medical school, it does expend substantial resources on medical programs and intensive science programs that are not offered at other USHE schools. Similarly, Utah State University, as the system’s Land Grant and Space Grant institution, offers agricultural, veterinary, and space-technology programs that are not provided at other institutions.

Programs that are in high demand by students, employers, and communities across that state are, of necessity, offered at multiple institutions to provide students with access to a comprehensive education. This especially includes high-demand liberal arts programs that provide a wide range of employment opportunities, as compared with more specialized programs with specific, less widely available, or geographically-focused employment outcomes. Education and nursing programs are also in critical need across the state.

Academic Program Approval

Because of this critical responsibility to ensure adequate program offerings across the state, the Board also has policies guiding the approval and review of instructional programs. The types of programs that USHE institutions offer are based on their institutional roles, missions, and the program parameters established in Board policies. State law requires the Board of Higher Education to delegate the authority to approve academic programs that fall within the defined institutional role to the appropriate Board of Trustees. Board Policy R401 outlines the approval process for academic programs and the parameters under which Trustees may approve programs. It defines the basic structure of certificates and degrees that degree-granting colleges and universities may offer, including the credit range allowed for specific degree types, whether the program must include general education requirements (which are explained in Policy R470), and distinctions between undergraduate and graduate programs.

State law specifies that the Board of Higher Education, not the Trustees, retains exclusive authority to approve “a degree, diploma, or certificate outside of the institution of higher education’s primary role, “if the Board is sufficiently satisfied with the “adequacy of the study for which the degree, diploma, or certificate is offered” (53B-16-103). The Board of Higher Education rather than the Board of Trustees must decide whether to approve:

- programs outside the institutional role;

- programs outside of the institution’s geographic service region;

- any new branches, extension centers, colleges, or professional schools.

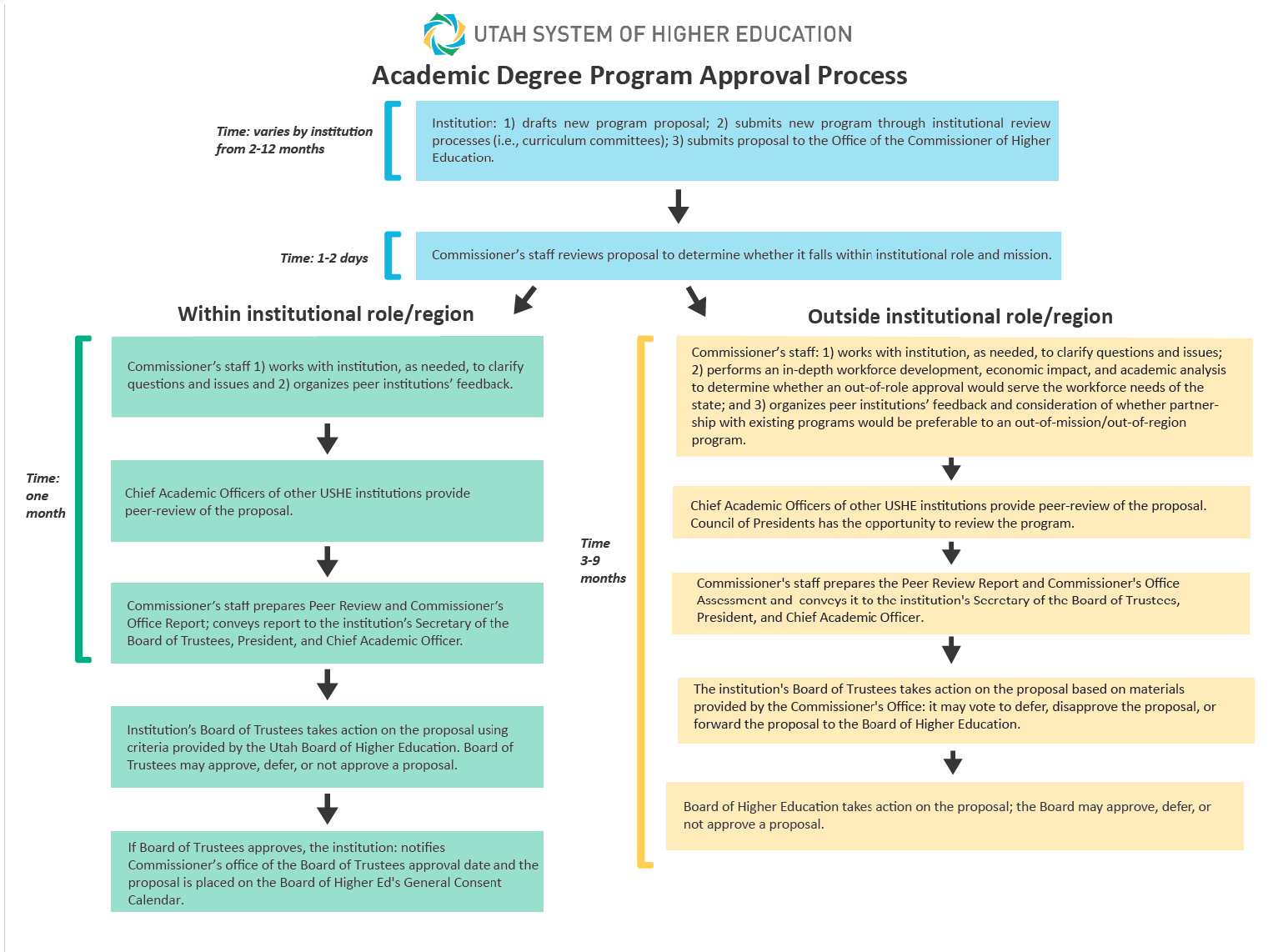

The Approval Process for Programs within the Defined Institutional Role: Boards of Trustees

Creating new degree programs most often begins within an academic department at a USHE college or university. Once a department has drafted its proposal, it must move through various levels of internal review at the institution, usually including the dean, the curriculum committee of its administrative unit (such as a “college” within a university or a “division” within a community college), the institution’s general education committee, an institutional-level curriculum committee, the provost’s office, and the budget office. These internal processes are defined by the institution itself.

Once a program proposal has passed through the various layers of internal review, it is forwarded to the Commissioner’s Office via a template based on Policy R401, which asks the department to provide detailed information about:

- institutional capacity, such as faculty, lab space, and other resources;

- the estimated economic impact of the program, including its budget/fiscal costs and potential revenue;

- equity and access considerations for students;

- local, regional, and state needs that the program will address;

- workforce demand and student interest;

- duplication of programs at other institutions;

- the possibility of partnering with existing programs at other institutions rather than introducing an independent program;

- national disciplinary norms and expectations;

- special program accreditation requirements, if any, and;

- transferability with other institutions in the system.

Once the template has been submitted, the Commissioner’s Office reviews it to determine fit within the institutional role, performs an assessment of the program, and also sends the proposal out for written peer review by sister USHE institutions. The Chief Academic Officers of all of the degree-granting institutions meet monthly to provide additional feedback on new program proposals and have a chance to ask questions of the proposing department. This feedback is crucial for identifying unnecessary duplication of programming, correcting possible weaknesses or accreditation challenges with the program’s design, and for offering support in helping to launch the program from affiliated faculty at other institutions. The Commissioner’s Office records the feedback from these meetings and provides all of the written comments, a summary of the oral comments, and drafts an overall assessment from the Commissioner’s Office. As part of their delegated responsibility from the Board of Higher Education, the Board of Trustees must use these assessments in their deliberations on approving the program. Once the Board of Trustees has approved a program, it is forwarded as an information item in the General Consent Calendar to the Board of Higher Education.

This process is designed to help departments, institutional committees, and boards of trustees carefully think through the investment of resources in new programs, including the possible need for new faculty, laboratory space or other physical plant needs, equipment, library materials, and expensive specialized accreditation.

The Approval Process for Out-of-Role Program Proposals: Board of Higher Education

Out-of-role program proposals undergo a much more intensive review by Commissioner’s Office staff, including a detailed workforce demand/labor market analysis, exploration into the possibility of partnering with other institutions instead of offering an out-of-role program, and efforts to determine whether the program may be better offered at a degree level already approved for the institution. Commissioner’s Office staff may contact accreditors, potential industry partners or employers, and USHE and non-USHE institutions for feedback as part of this assessment. Out-of-role program proposals also undergo the peer review process with sister institutions. The Commissioner’s Office sends the outcomes and details of all of those reviews to the institutional Board of Trustees along with a recommendation. If the Trustees vote to proceed with the program, it is forwarded to the Board of Higher Education for final approval.

There have only been five out-of-mission programs approved within the system, all based on regional workforce needs. This includes two bachelor’s degrees at Snow College and three clinical doctoral programs at regional universities for occupations where employment demands were shifting from master’s degrees to doctorates. However, because state code specifies that “it is not the intent of the Legislature to increase the number of research universities in the state beyond the University of Utah and Utah State University,” the Board has never approved an out-of-role research doctorate (53B-1-102).

Cyclical Program Review

Once a program has been approved by either the Trustees or the Board of Higher Education, it must undergo regular cyclical program reviews to ensure it is performing adequately. The process is outlined in Board Policy R411. The Commissioner’s Office performs an initial review of a program, in consultation with the institution, 2-3 years after the program is offered to the first cohort of students in order to gauge whether it has launched successfully. Once degree programs are in operation, they are reviewed every seven years. Those cyclical reviews include internal institutional assessments based on criteria established by the Board; institutions are also required to solicit and forward evaluations performed by external evaluators from non-USHE institutions and any special reviews required by program accreditors. Disciplines across the system will also be collectively reviewed to determine whether there is unnecessary duplication between institutions and whether there is sufficient enrollment to justify multiple programs.

In 2021, the Commissioner’s Office established more stringent responses to programs that are struggling with enrollment, student completion outcomes, faculty hiring, specialized accreditation, or other difficulties. The new process includes working with the provosts of sponsoring institutions to place struggling programs on probation and identifying clear benchmarks that must be reached and reported on to the Board of Higher Education within a specified period of time (generally one year). If the program has not met the required benchmarks by the established deadline, the program will be discussed by the Board, which may require its termination. Programs that are performing adequately are listed on the Board’s General Consent Calendar.

Institutions also conduct their own periodic reviews and may decide to terminate programs. These actions are also listed on the Board’s General Consent Calendar.