Higher education leaders across the country have long-wrestled with improving student retention and degree completion. A new national report highlights the disparity between the intentions of college students and their often short-term impulses, especially during their first year of college. The report, from non-profit research organization ideas42, focuses on behavioral science—applying insights from psychology and other social sciences—to address real world policy issues in higher education.

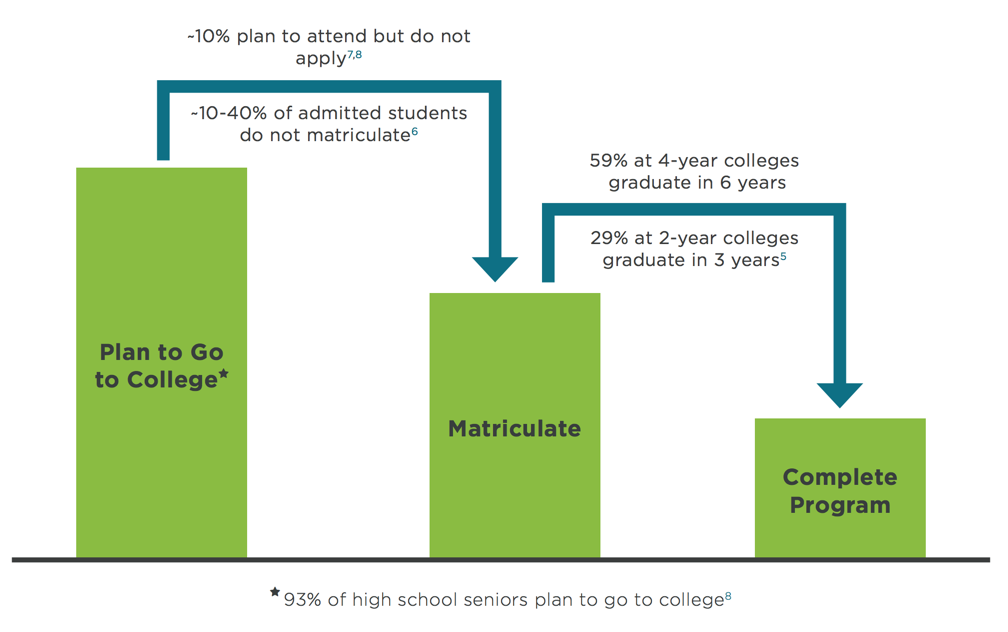

- 93% of high school seniors say they intend to go to college, but 1 in 10 of those never apply.

- Between 10 and 15% of those who are admitted never register for classes.

- Of those who do show up, only 59% of four-year college freshmen, and just 29% of two-year college freshmen, actually get their diploma in a reasonable length of time.

Their new report, Nudging for Success, outlines 16 specific behavioral barriers that prevent students from succeeding in college using real-world data-driven case studies in five primary categories:

- Pre-Admissions: Making it to Day 1

- Affordability & Financial Aid

- Connecting on Campus

- The Balancing Act: Getting to Graduation Day on Time

- Post-Graduation Day: Get on Track to Pay It Back

These case studies reflect a recent national trend among higher education institutions to better use data to understand student behavior in navigating the college experience.

College completion is a crisis

In 2013, Board of Regents adopted a five-tiered strategy to improve student completion at USHE institutions, which is also one of three keystone metrics of A State of Opportunity, the 10-year strategic plan adopted by the Board of Regents in early 2016. Similarly, level42’s report concludes in its opening statement, “It’s clear that there’s a completion crisis in American higher education.” However, the report goes beyond the obvious completion barriers such as tuition, poor academic preparation, and the ofttimes competing obligations of family or work: “the student path through college to graduation day is strewn with subtle, often invisible barriers that, over time, hinder students’ progress and cause some of them to drop out entirely.”

The case studies within the report focus on simple procedures to help students navigate the logistical hurdles associated with college including financial aid, admissions, course registration, and academic probation.

Improved communication to students

level 42’s case studies focused primarily on more effective communications to students—and their parents. For example, Arizona State University (ASU) was interested in getting returning students to file their Free Applications for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) on time. Researchers discovered many students mistakenly associate the FAFSA with just initially applying for college and weren’t aware that it’s due every year.

Researchers worked with ASU on a series of strategically timed emails to communicate the details of federal aid opportunities in more manageable steps. In addition, a subset of students’ parents also received reminder emails, something the financial aid office had never done.

The concept proved successful. When both parents and students received emails, half of the students filled out their financial aid for by the priority deadline and received, on average, $643 more in gift aid (not loans). By comparison, just 18% of students at ASU met the federal financial aid deadline the previous year.

Other initiatives included increased “early-bird” advising to decrease course withdrawal rates, reduced academic violations through proactive personalized messaging, and personalized messaging on class attendance behaviors.

The USHE perspective

In addition to the five statewide strategies aimed at improving college completion, USHE institutions have been implementing similar data-driven initiatives to help remove the subtle yet obtrusive barriers students face in successfully completing college. For example, at Utah Valley University, students are placed on “early alert status” when not making adequate progress towards course completion, and a hold may even be placed on the student’s registration the following semester until they meet with an advisor. At Southern Utah University, a student whose GPA drops below 2.0 is required to make an academic recovery plan with customized referrals from advisors to specific services. Dixie State University is piloting a first-year learning community program for Fall 2016 to support students as they transition to college life. The program places students in cohort-based peer support groups of 25 to help them as they complete their general education courses together. Salt Lake Community College has started its Bridge to Success, a three-day intensive course a few weeks before the fall semester to help students transition to the college experience, with an emphasis on math readiness. The University of Utah recently introduced its Mandatory Advising Program, requiring all first year students to meet with an advisor before they are allowed to register for classes their first Fall semester.

These handful of examples demonstrate the awareness among USHE institutions that a successful first-year transition, with proactive and intervention-based advising, can help students overcome the subtle and often unseen barriers to college success, especially during their first year of college.