In the wake of the Great Recession, a common refrain took hold: That of the overeducated barista, unable to find a job in their field, working instead in a low or middle-skilled position just to get by. By 2012, more than half of college graduates under age 25 were jobless or underemployed.

Underemployment, while not always clearly defined, generally refers to workers who feel they are underpaid for the skill or education they have. The most common method of measuring underemployment is by the number of individuals with bachelor’s degrees who work in fields during the five years after graduation that typically don’t require that level of education for entry.

But, were recent grads really stuck in these jobs that were so far beneath them? A new study from the New York Federal Reserve finds that the reality is students with a college degree were able to best weather the economic challenges of the Great Recession. In fact, the Fed’s study found that underemployment is mostly a transitory state — the percentage of 22-year-old college grads working in low-skilled service jobs falls from 13% to about 6.7% by the time they’re 27.

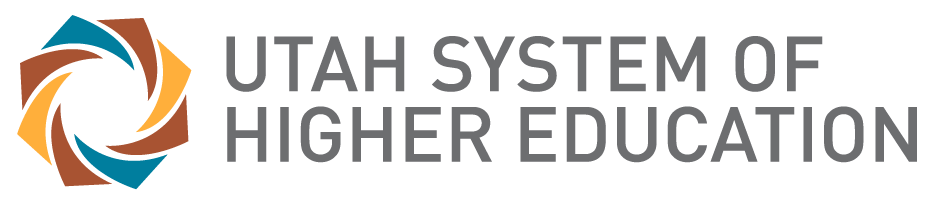

Underemployment since 1990

While the number of underemployed college graduates spiked following the recession, it is not a new phenomenon: the proportion of people within five years of graduating from college working in jobs that didn’t require a college degree actually peaked in the early 1990’s, at above 47%. It fell dramatically thereafter, rose sharply in the mid-2000’s, dropped again, rose in the recession, and has been mostly dropping since 2014.

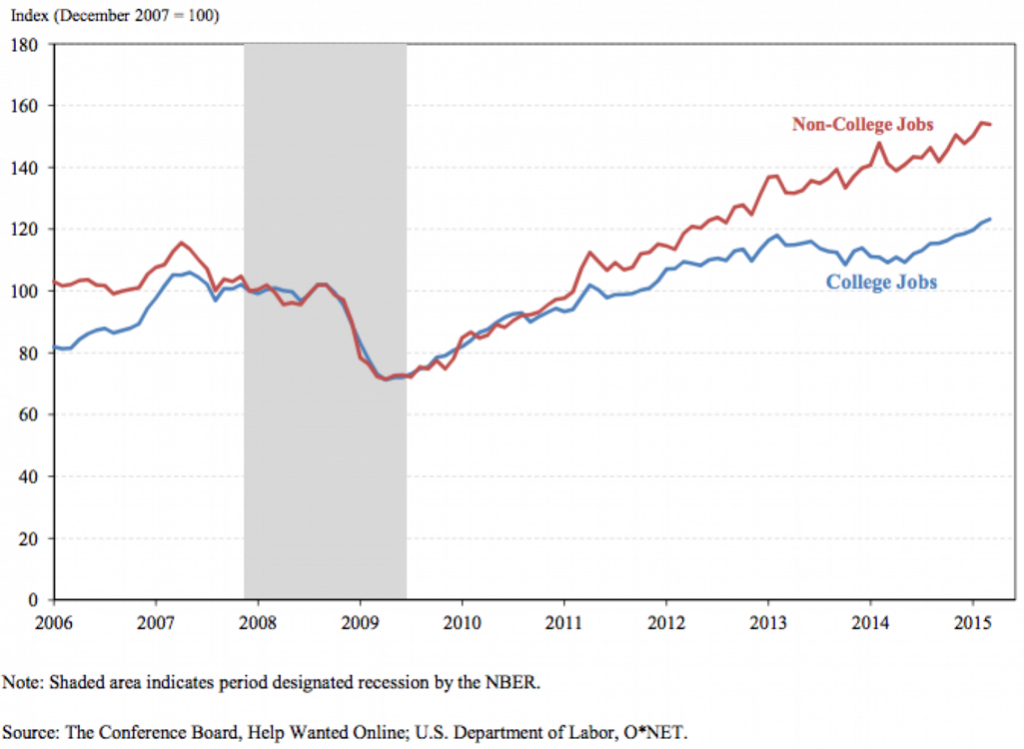

Demand for college graduates through the Recession

Complicating the underemployment picture is that jobs for the less-educated grew faster than those for the more-educated, starting as the nation’s economy emerged from recession. In other words, if new graduates ended up underemployed in the years immediately following the recession, it’s in part because those were the easier jobs to get.

Utah is no exception. The state’s economy in the most recent recent years is facing the same challenge: according to the U.S. Census, Utah and Davis counties were among the top ten counties in job growth between 2014 and 2015. The industries that grew the most were trade, transportation, and utilities – all industries with generally lower wages and low education requirements. Overall half of all employed Utahns currently work in industries with median wages less than $35,000 annually, according to the Utah Department of Workforce Services.

A recent report by the Utah Foundation analyzed how employees and employers in Utah stack up against their out-of-state counterparts. The analysis found 71% of companies reported some level of difficulty finding enough skilled or qualified employees. The report also cited data from a recent survey by the Utah Department of Workforce Service that found 68% of companies are offering below-median wages for difficult-to-fill positions.

Increasing educational attainment increases wages, decreases underemployment

Together, these statistics demonstrate a primary factor contributing to underemployment: wage stagnation. While wages since the recession have started to rise nominally, they are primarily keeping with inflation. In the, U.S., since 2007, wages among young people have dropped in all industries with the exception of healthcare. Educational attainment correlates with increased wages: an additional recent study found the share of adults with graduate or professional degrees is closely associated with the concentration of high-tech industry (.67) and the rate of innovation (.64).

A December editorial by the Salt Lake Tribune highlights a key policy lever state leaders can use to help increase wages and strengthen Utah’s economy: more investment in education. The conclusions by the Tribune and the New York Fed are the same: increased educational attainment makes for a better-skilled workforce which leads to decreased underemployment of students, increased wages, and overall economic growth beyond just increased jobs.